By Ed Odeven

TOKYO (March 11, 2018) — Fifty years after Jackie Robinson’s first game with the Brooklyn Dodgers, Major League Baseball honored the historic day in American history on April 15, 1997. It’s one of my all-time favorite days in sports history, even if the Hall of Famer wasn’t alive to observe this special day.

Since then, Robinson’s legacy as the man who broke MLB’s color barrier continues to be honored and discussed.

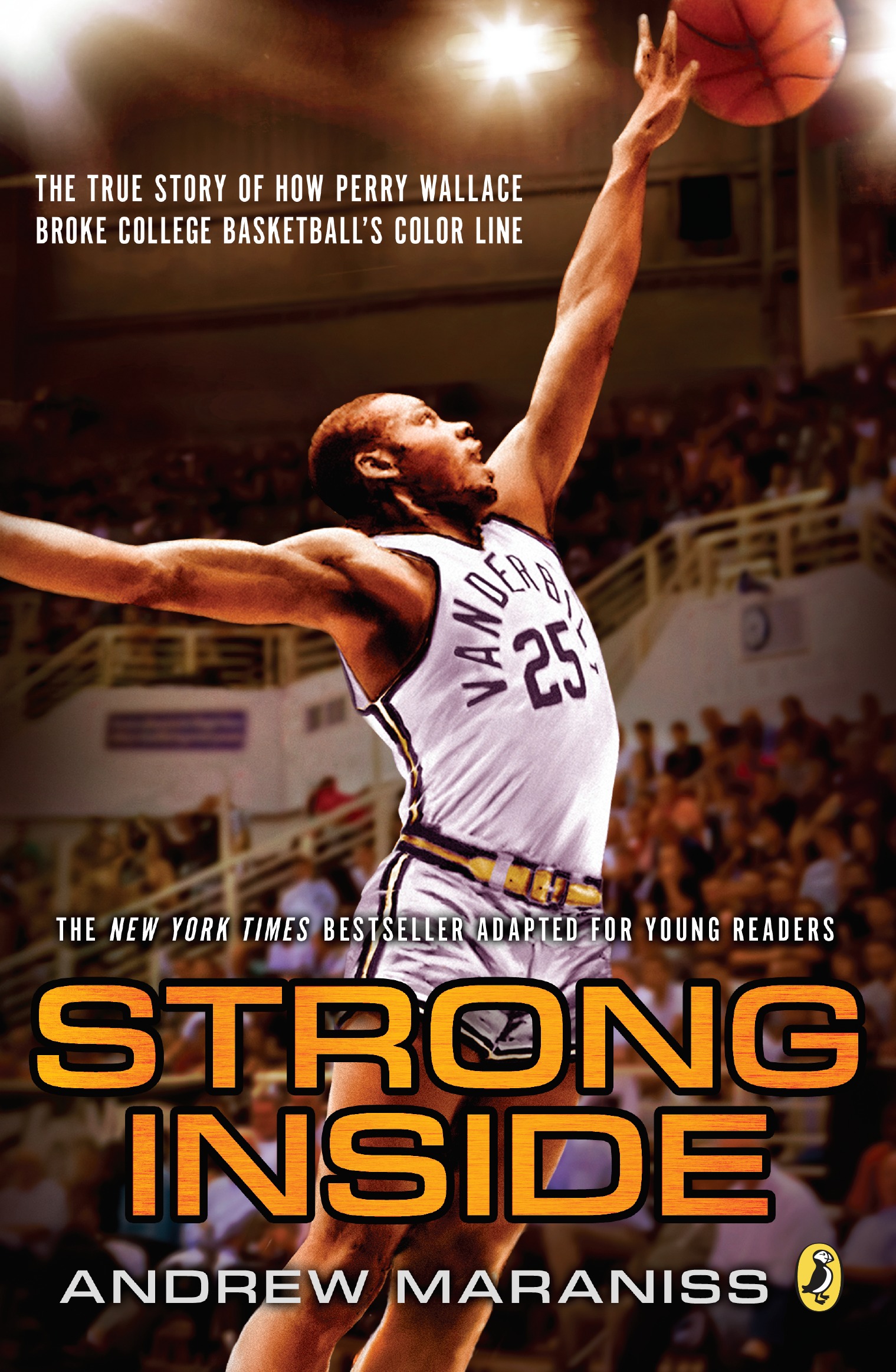

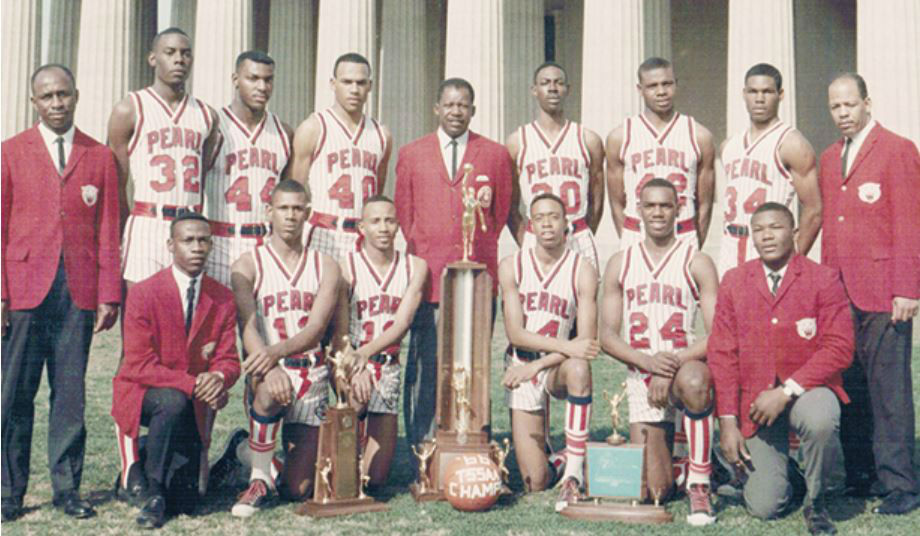

Other sports figures, of course, helped pave the way for the racial integration of college and pro sports in the United States. One of the most important individuals was former Vanderbilt University basketball player Perry Wallace, who was the first black to compete on a Southeastern Conference basketball court. The native of Nashville, Tennessee, did so from 1967-70. (In 2004, his No. 25 jersey was retired by Vandy.)

In a recent interview, Andrew Maraniss, author of a fascinating and important biography, “Strong Inside,” on Wallace looks back on the project, provides great insights on Wallance’s remarkable life and the strength of his character and deep moral convictions.

Maraniss exhibited admirable dedication and persistence in completing the project. It took him eight years to research and write his first book. By doing so, he joined his father, legendary journalist and biographer David Maraniss, as a published author.

Wallace passed away on Dec. 1, 2017. He was 69.

Maraniss delivered the eulogy for his friend, hero and mentor in February.

In his life, Wallace shattered stereotypes about ex-athletes. For the U.S. Department of Justice, Wallace worked as a trial attorney, and became a law professor at American University. Maraniss’ book captures the essence of Wallace’s life and offers insights about his intelligence, courage and common decency, among other attributes.

***

Above all, how has Perry Wallace shaped your outlook on life?

I knew Perry for nearly 30 years and he changed my life in so many ways it is impossible to list them all. He was like a combination of a mentor, brother, father, and favorite professor, not to mention the subject of my book. He was a remarkable person whether or not he ever made history as a sports pioneer. That’s been one of the challenges of explaining STRONG INSIDE to people. The quickest and easiest way to describe it is that it’s a biography of the first African-American basketball player in the Southeastern Conference. Ho hum. But Perry was so much more than that. He was the kind of person who quoted Othello when making a point. He sang opera. He spoke multiple languages, including fluent French. He was the rare law school professor who had been drafted by an NBA team. He loved martial arts. He had witnessed the lunch-counter sit-ins first-hand as a 12-year-old kid in Nashville. He met and spoke with civil rights figures in the ’60s such as Martin Luther King, Stokely Carmichael, Fannie Lou Hamer and Robert F. Kennedy. He served in the National Guard and was an attorney for the U.S. Justice Department. He was the first black basketball player ever to play at Ole Miss or Mississippi State, tremendously dangerous places to be in 1967. He had uncommon wisdom on race, racism, and race relations. He also had great advice on fatherhood. He turned down scholarship offers to colleges that offered him cash and cars and told him he didn’t have to go to class. He traveled to Nigeria to help save the life of a woman sentenced to death. He testified before the United Nations. He could throw down a reverse slam dunk and jump so high he could pick up a quarter off the top of the backboard. His last words to me were to look for ways to create opportunities for women. Think about all this. One man! It’s incredible. In every possible way, he was an inspiration. As one of his law school colleagues at American University said, he was the best in all of us, the best side of any one of us, our best selves. The rest of us fall so far short, but Perry was the real deal.

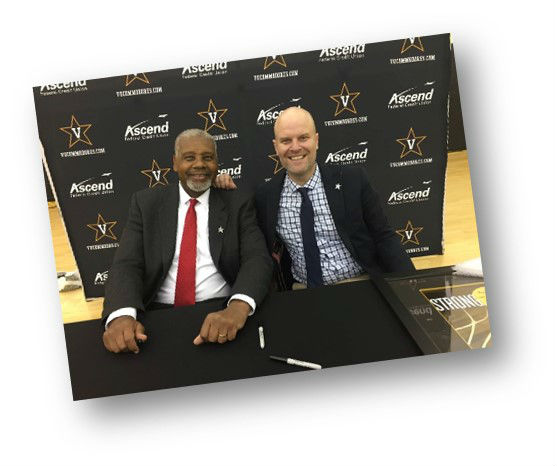

Perry Wallace and Andrew Maraniss

How significant, or perhaps how touching is it for you that iconic journalist Bob Woodward delivered the following message about your book?: “In a magnificently reported, nuanced but raw account of basketball and racism in the South during the 1960s, Andrew Maraniss tells the story of Perry Wallace’s struggle, loneliness, perseverance and eventual self-realization. A rare story about physical and intellectual courage that is both shocking and triumphant.”

This was indeed very touching. Mr. Woodward has been a very close friend of my parents ever since my father joined The Washington Post in the mid-1970s. I met him for the first time when I was 6 years old. I remember he was the first person to ever show me a Sony Walkman! When I put the headphones on, I was stunned nobody else could hear the music. He also brought me and my sister some 45-rpm records one time when he visited our house. I remember Safety Dance was one of the songs! So to know him as a child on top of all the respect I have for him as such a significant journalist and figure in American history, it was indeed a great honor to know that he read STRONG INSIDE and had kind things to say about it. As a first-time author, it helped develop some credibility. I also remember how great it felt when I received an email from Frank Deford with his blurb for the book. He’s not someone I had known previously. Given his stature as an iconic sports journalist, that was very meaningful to me as well.

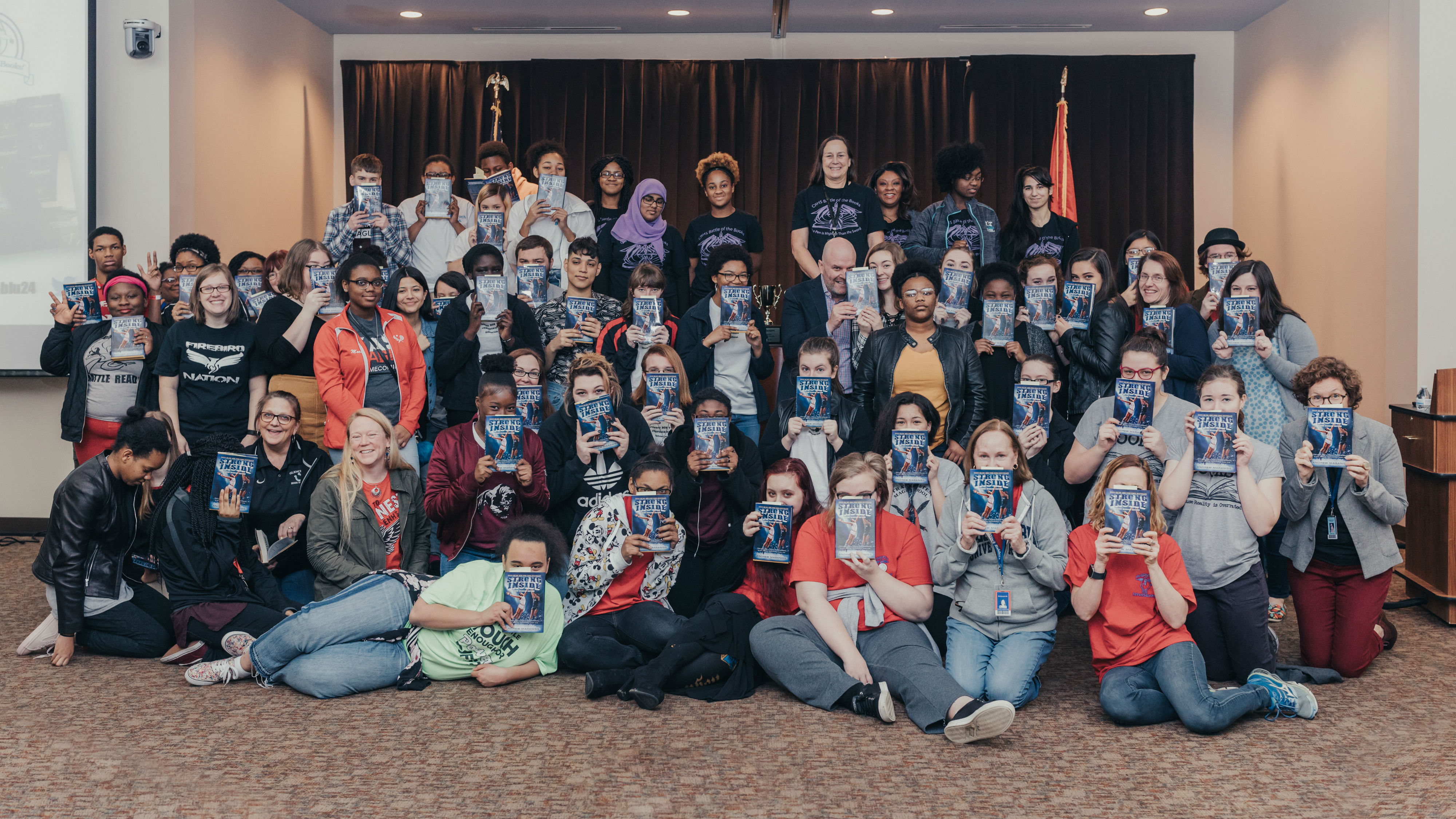

As you make visits to schools and civic organizations to speak about your book and Wallace’s life experiences, how would you characterize the general reaction from students about your message? Have you been touched and inspired by their questions and their overall curiosity about your project and Wallace?

This has been the most amazing part of my experience as a new author, and one that I hadn’t anticipated. I really love traveling around telling Perry’s story, and it has been touching how very disparate audiences have reacted to the book. I’ve been to 19 states, and the audiences I’ve spoken to have been incredibly diverse: from civic clubs in rural Tennessee to a school for the deaf in Texas to a program for Latino and African-American high school young men in New York City to a boarding school in Chattanooga to the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis to a book festival in Des Moines and many, many more. I’ve spoken to four-year-old pre-school students and at retirement homes. I’ve spoken in a maximum security prison and in a few churches. The reaction has been very, very gratifying. It’s no surprise that people are drawn to Perry’s story of perseverance, grace, and wisdom. He was a very special person and people recognize and appreciate that — no matter their background. It’s not uncommon for me to see people crying. A couple of schools in Nashville have used the book for “all school read” projects. Vanderbilt has required incoming freshmen to read the book each of the last two years.

A few other things come to mind:

- When Perry Wallace was a freshman, he began attending a white Church of Christ across the street from campus upon the recommendation of a teammate. Perry said that growing up in Nashville, he never would have considered going to a white church, but that this was what pioneering was all about: doing things that hadn’t been done before. So he starts going, but around the fourth Sunday, some members of the church pull him aside and tell him he can’t keep coming anymore. They say older members of the church have threatened to write the church out of their wills if they allow Perry to keep attending. So he’s kicked out. Fast-forward to this year and a Church of Christ middle school in Nashville, Lipscomb Academy, selected STRONG INSIDE as it’s required read for all of its students. These are the literal and figurative descendants of the people who kicked Perry out. It was amazing to see the way these kids fell in love with Perry and embraced his story. Two of Perry’s sisters visited the school for an assembly and they received a standing ovation and a long line of hugs from the students.

- A group of special students in Cleveland, Ohio, read STRONG INSIDE and decided to come all the way to Nashville to visit the important sites in Perry Wallace’s life. What makes this all the more remarkable is that these young people have Downs Syndrome and Asperger’s and other exceptionalities. Their teacher told me that Perry has become a real inspiration to her students, who are battling various challenges every day. When they encounter hard times, they ask themselves, “What would Perry Wallace do in this situation?” And she said they always remind themselves that what he would do is remain “strong inside.” Incredible.

- Last year, I had a chance to meet all the first-year international students at Vanderbilt the night before classes started. One young man from China came up to me and said that he had read STRONG INSIDE before making his decision whether to come to Vanderbilt. He said that after reading the book, he had decided that if Perry Wallace could make it at Vandy, he could, too.

- Perry and I spoke at the Maret School in Washington, D.C. two years ago. The students there loved him. This year, I saw a girl on campus wearing a Maret T-shirt. I asked her about it and she said that she was a freshman and that after hearing Perry talk at her school, she was inspired to apply to Vanderbilt.

- I spoke to a third-grade class in Nashville yesterday. It was “Super Hero Day” and all the kids were dressed up in cute costumes. One little girl was dressed up like a pilot, but she told me she had read STRONG INSIDE 10 times and that Perry was her hero.

Originally, did you have the intention of making a Young Readers edition of Strong Inside? If so, why was that an important goal after the first version of the book was produced? If not, what prompted you to make the new adaptation of it in 2017?

I didn’t have that vision when I wrote the original edition of STRONG INSIDE. It was not something that had ever occurred to me over the entire eight years I spent working on the book. I have two amazing women in Nashville to thank for the inspiration to do it. One is Ann Neely, a highly regarded professor of children’s literature at Vanderbilt University’s Peabody School of Education. Ann is someone I’ve known for more than 20 years, dating back to the time I was the sports information director for the Vanderbilt basketball team and she ran the academic center in the athletic department. After STRONG INSIDE came out, she suggested it would make a great story for young people. Then there was Ruta Sepetys, a best-selling author of historical fiction for Young Adults. Ruta was sitting in a coffee shop in Nashville doing a newspaper interview to discuss her book “Salt to the Sea” when the reporter, Keith Ryan Cartwright, introduced the two of us. Ruta is not only a fantastic writer, she’s the nicest person in the world. She interrupted her interview to talk to me for 15 minutes about my book, and by the end of the conversation she had offered to send a copy of STRONG INSIDE to her publisher along with her endorsement. Within just a few weeks, I heard back from the editor at Philomel (Penguin Young Readers Group) saying he wanted to adapt the book.

An eight-year project from start to finish shows discipline and dedication and persistence. Were there times during that period that you honestly thought you wouldn’t finish writing Strong Inside? Are there a few voices of inspiration you’d like to mention who kept you focused and striving to get it done during those years?

I was fortunate to be very naïve about the process of writing a book when I got started. Ignorance was bliss! I had no idea when I got started in 2006 how long it would take to complete the project, and honestly I didn’t care. Because I didn’t have an agent or a publishing deal, I wasn’t under any sort of deadline pressure. The entire time I worked on the book, it was a side project outside of a regular “day job’”at a public relations firm in Nashville. For the first four years, I didn’t write a word; it was just research and interviews. I loved that aspect of the project. I’m very happy scrolling through microfilm. This was the period, however, where the book seemed more like a dream than an actual tangible product. There would be weeks or entire months where I wouldn’t get much done. As I completed the research and began writing, the biggest mental hurdle I had to overcome was the idea of writing something so long. I’d never written anything longer than a magazine article. STRONG INSIDE turned out to be around 200,000 words. Once I had written one chapter, I just said to myself, “If I can write one, I can write two.” And then it was, “If I can write two, I can write four.” I convinced myself that all I had to do was stay disciplined and patient and eventually I would complete the book.

One of the things that kept me going was Perry Wallace; both my incredible respect for him and also just his own story of perseverance. If he could overcome all the challenges he faced in his life, there was no excuse for me to feel overwhelmed by simply trying to write a book. Beyond that, my wife, Alison, my parents, David and Linda, and my in-laws Doug and Cathy were constant sources of support.

Do you recall when you first met Perry Wallace? Where was it? Was that initial encounter significant for you in pursuing this project? Or did living in Nashville and attending Vanderbilt, being immersed in a place where his history was so alive, contribute greatly to your decision to write a book on him?

The first time I met Perry Wallace as in Atlanta at the SEC basketball tournament in 2004. But that wasn’t the first time I talked to him. My initial interest in him and the first time I spoke to him came in 1989, when I was a sophomore at Vanderbilt. This also happened to be the year that he was invited back to campus for the very first time since graduating in 1970. A student a year older than me, Dave Sheinin (now an outstanding writer at The Washington Post) wrote an article about Perry for a literary magazine at Vanderbilt. He described the first game Perry ever played at Mississippi State as a freshman, and how scary that experience was in Starkville, Mississippi in 1967. As a sports nut and a history major taking a course in African-American history, I was hooked. I asked my professor, Dr. Yollette Jones, if I could write a paper about Perry. I thought she’d say no, that sports wasn’t a serious enough topic. Thankfully, she said if that’s what you’re interested in doing, go for it. Back then, of course, there was no Google or email so I found Perry in the phone book. He was a professor living in Maryland. I called him out of the blue and introduced myself and he spent two hours talking to me about his experience as a pioneer. So, I wrote my paper and Dr. Jones gave me some really nice feedback. I felt like I was on to something. The next year, I wrote another paper about Perry for a similar class. I became sports editor of the student newspaper and wrote some columns about Perry, introducing him to my generation of students.

After I graduated, my first job was as the publicist for the Vanderbilt men’s basketball team. That gave me an excuse to stay in touch with Perry, nominating him for various anniversary awards. But again, that was all done over the phone.

Finally, in 2004 I was in Atlanta for the tournament just as a fan. Perry was being honored as an SEC legend that year. I was leaving the Georgia Dome one day and saw him waiting for a shuttle bus. So I went up and introduced myself. Two years later, I was standing in my future in-laws’ kitchen in Nashville. I declared that I wanted to write a book, but didn’t know what to write about. My future father-in-law said, “What about Perry Wallace? You’re always talking about him.” And that was the Eureka moment. I said, yes, that’s it, and I got started the next day.

Back to part of your question: the truth is that Perry’s story wasn’t all that alive in Nashville. As I mentioned, he graduated in 1970 and wasn’t invited back to be honored as the Jackie Robinson of the SEC until 1989. The reason for that is a story that still resonates today: essentially, he was told to “shut up and dribble,” just like the FOX talking head Laura Ingraham told LeBron James. The day after Wallace’s last game in March of 1970, he gave an interview to the local newspaper where he talked about his experience as a pioneer. It was an honest interview, and he discussed the racism and isolation he experienced on campus. He suspected that people weren’t going to want to hear this difficult truth, but he felt he had a moral obligation, as a pioneer, to tell the truth for the benefit of the people that would come behind him, and for the benefit of the university.

After the story ran, Wallace was labeled as “angry” and the university kept its distance for almost two decades. One of the most gratifying things that happened over the last decade of Wallace’s life was the complete turn-around in his relationship with Vanderbilt. The school embraced him and he welcomed that. He used to say that “reconciliation without the truth is just acting,” and he felt that this was a real reconciliation, one where the truth was accounted for and appreciated.

Was he eager, excited, intrigued by your book project? Did he approach you about writing it? Did you approach him? Was it a mutual idea you both sort of came up with after being around one another for X number of hours over the years?

When I emailed Perry in 2006 to re-introduce myself and let him know that I was interested in writing a biography about him, he was very supportive. He remembered me and the paper I had written about him, and I think he also respected my father’s work at The Washington Post. I’m sure there was some doubt in Perry’s mind initially about how serious I was about this, would it really happen, etc., but he was always very, very supportive. He was the subject of the book but also a mentor to me in many ways. And even though it took me eight years to complete the project, he never became impatient. It was a wonderful experience. The bonus of it taking so long was that I got to spend so much more time talking to him. I would fly to DC to see him or he’d come to Nashville. We’d also talk on the phone, and sometimes I’d email him a set of questions and I’d be so excited to see his name in my inbox with his responses.

How instrumental has your father’s work as a prominent journalist who has reported on history and historic figures been in steering you in this path, in influencing you about how to approach this project? And was he a real critical eye in critiquing your work along the way, or more a listening board whom you bounced ideas off of to get some clarity and focus?

I grew up reading my dad’s stories in The Washington Post and also reading other great writing in that paper, so that was a huge influence in my life and my writing style, really without even being aware of it. It was more like through osmosis that I was learning how to write just by reading great writing. My dad wrote his first book after I had graduated from college. On a few of his projects, such as for his biography on Roberto Clemente and his book on the 1960 Olympics, I had the opportunity to do some research for him or conduct some interviews. Those were great learning experiences for me. Just as a reader, the types of books he writes are the kind I’m most interested in. I’m sure that’s no coincidence. Narrative non-fiction is my favorite style. I learned from him the importance of doing the real work, meaning the research and the interviews and traveling to important places in the book. He was more of a sounding board and big-picture guy when it came to my book. My mom was more active in providing line edits and that sort of thing.

What are the biggest journalism principles he bestowed upon you? Does one stand out above all the others?

Avoid clichés. Avoid unnecessary words. Do the reporting. Unpack the story. Go there (as in travel to important places in the story). Illustrate the universal through the particular. Pay attention to leads and kickers. They were all important lessons.

Since Wallace’s days as a collegiate player ended, who are a few college and pro players whose skill sets and on-court ability and impact closely mirror what he brought to Vandy?

There aren’t many 6-5 centers in college or the NBA these days! Perry was a fantastic rebounder, shot-blocker and dunker (until the dunk was banned in college basketball prior to his sophomore season). He wasn’t a great shooter, but he worked on his shooting tirelessly. By his senior season at Vanderbilt, he was the one the coach selected to shoot free throws on technical fouls, and he was very proud of that. Someone like Charles Barkley comes to mind as an undersized rebounder, but Perry was a better leaper and not quite as much of a wide-body. This is a good question and one I wish I had asked Perry – who reminds you of yourself?

You cited Jackie Robinson and the question of what if no one had written a book on him on your website in the trailer for Strong Inside. Now that two editions of Strong Inside have been produced, what’s the general feeling you have about what the book has accomplished for both sets of audiences? Is there a persistent satisfaction in knowing the book can and will educate folks and also change some people’s minds in terms of stereotypes about so-called “typical” athletes?

I like listening to a light-hearted podcast where the hosts follow-up every self-serving statement by saying, “not to brag.” So, “not to brag,” but I was very proud that STRONG INSIDE received two civil rights book awards, the Lillian Smith Book Award and the RFK Book Awards’ Special Recognition Prize. To me, this was evidence that the book was taken seriously as far more than a sports book. And then the Young Readers edition was named one of the Top 10 Biographies for Young Readers in 2017 by the American Library Association. Again, evidence that even for kids, this was more than a sports book. And all of that is to say that I have been very happy that people have recognized Perry Wallace’s impact well beyond the basketball court.

I’ve spoken to adults and seen contemporaries of Perry’s crying in the back of the room. I’ve listened to elementary school kids talk about how they can’t comprehend the racism Perry endured. So, yes, this is satisfying to see the emotional impact of the book, and perhaps to have people think about race in a way they weren’t expecting when they picked up a biography of a basketball player. Most of all, I’m pleased that Perry’s story is known. I talk to kids about the movie Hidden Figures, and how there are so many other hidden figures out there, people who have done important and interesting things whose stories haven’t been told yet. Any one of us can be the person to unearth those stories and tell them to the world. I feel very fortunate to have been able to write about Perry and introduce his story to people who had not heard of him.

In addition to Wallace, who are some other absolutely invaluable sources for the book? According to a 2014 news release, you interviewed more than 80 people for the project. Did you travel far and wide to do that?

I ended up interviewing around 100 people for the book, and that was one of my favorite parts of the whole project. I really enjoy preparing for and conducting interviews, and there’s nothing like the feeling when someone starts telling you an interesting, colorful, detailed anecdote that you know is going to make a great scene in the book. I traveled some to conduct interviews and also did quite a few over the phone. I was also lucky that most of the book takes place in Nashville, where I live. So many of the people I needed to interview for the book live here. Some of the most fascinating interviews were with Godfrey Dillard, who was Perry’s only African-American teammate during his freshman year. Dillard ended up transferring before playing a varsity game, and his experience at Vanderbilt provided an interesting contrast to Wallace’s in many ways. I was also fortunate that Perry’s college coach, Roy Skinner, was still living when I started working on the book. He was the first person I interviewed. I also had the great pleasure and honor to interview John Seigenthaler, who was the editor of the Tennessean at the time Wallace was in college. Mr. Seigenthaler was a staunch supporter of civil rights and had served as a special assistant to Robert F. Kennedy during the Freedom Rides.

What was it like interviewing Wallace for his life story? Was he very forthcoming and quick with details in interview settings? Did you throw out a general topic and just let him recollect about it for a while? Was there a lot of very specific questioning?

I tried to be very prepared for our interviews, but I also went in with an open mind and tried not to stick too closely to a prepared script or list of questions. Perry was such a brilliant person that it was not difficult to interview him at all. He was a great observer of people and situations and had the ability not only to recollect details, but also to put anecdotes into a greater context. He not only helped you envision a scene from 1968, for example, but would place a particular story into the context of the times. He had such wisdom when it came to race relations. So, many times we’d start a conversation and I’d just sit back and listen. The biggest mistake I could make was getting in the way. With someone like Perry, just let him talk. And really listen, so that you can ask good follow-up questions. That’s an interesting insight you make about him being a lawyer and using precise language. That is true. But Perry was also precise with his language well before he went to law school. I found a transcript of remarks he made to the Vanderbilt administration in the summer of 1968 and it was expertly crafted. Perry was a brilliant person and he took pleasure in disproving stereotypes, even at a young age. Part of that meant being prepared, being precise, being profound.

Did you have regular weekly/monthly interview sessions lined up with Wallace as you formulated the book? Did you often meet him at his home or workplace? A favorite restaurant? Long phone chats? What worked for both of you to get the questions asked and answered? Was it a combination of all of the above?

We didn’t have any sort of regular schedule. We had four or five major in-person interviews at the outset of the project, where we divided his life up into chunks and covered ground in particular areas each time. Some of those interviews were done in Washington, D.C., where he lives and where my parents live, either at his office at American University or at my parents’ house. We did one or two in a coffee shop. Other interviews were done in Nashville. I remember one of my favorite days was just driving around with him all day, and he showed me the houses he grew up in, the parks he played in, the schools he attended. We also did several phone interviews, and eventually his favorite way to do it was over email. I’d send him a list of questions, and then a few days later I’d get a response back. His quiet time at home was around 4 a.m., so that was the timestamp on so many of his replies. Which were always detailed and brilliant, by the way.

How emotional, how challenging, was it to deliver the eulogy on Feb. 20 at Vanderbilt for Perry Wallace? Was it a cathartic experience to share your thoughts about his life and legacy with an attentive audience?

The most challenging aspect was figuring out what aspect of Perry’s life to focus on since I only had three or four minutes to speak. We called the event a “Celebration of Life,” so there was a focus on keeping it upbeat and celebratory rather than maudlin. I decided to talk about a few things: just how a good of a man Perry Wallace was his entire life when there seems to be a lack of good men, at least in terms of public figures, these days. And I talked about how he might use such an event had he been alive: he would turn the spotlight away from himself and use the occasion to try to make life better for other people. It was special to see the caliber of people who not only came to the service, but wanted to speak: the commissioner of the Southeastern Conference and the chancellor of Vanderbilt University, for example. This was important in substance and symbol, and really demonstrated what an incredible impact Perry Wallace had on the university and the South.

Are you currently pursuing a new book project? Or is there a topic that intrigues you that you’d be interesting in writing about in the coming years?

Yes, I am in the final stages of writing a book for Young Readers on the first U.S. Olympic basketball team, which played at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin. What I’d like to do is continue to write the kinds of books I would have liked to have read as a student: narrative non-fiction, with a bent toward sports and history.

How did the daily grind of working in sports media relations for Vandy and the Tampa Bay Devil Rays sharpen your focus and self-discipline as a writer and journalist? And looking back, how did that help you as you wrote about Wallace?

That’s a really interesting question I’ve never been asked before. I think of a couple of things. For one, I never worked harder in my life than I did in those days (or for less money!). As you mentioned, it is an incredible grind, day after day. So I learned how to work hard, how to be creative every single day, the importance of accuracy. I had great bosses who were mentors to me and gave me confidence that I could succeed in the business. Obviously working as a publicist for the Vanderbilt basketball team gave me an appreciation for the history of the program, access to former players and coaches, and various anecdotes over the years that helped me with little details for STRONG INSIDE. I felt like I understood the history of the program inside and out. When I was writing the basketball scenes in the book, I felt like my professional background and just my interest in sports allowed me to write with authenticity and credibility.

Is there a greater appreciation of, and recognition of, the incomprehensible challenges that Wallace faced during his time at Vandy and in the SEC since he passed away in December?

I’d say that the appreciation for what Perry endured really began several years ago. Over the last 10 years of his life or so, you began to see the university and the Nashville community reach out to Perry in ways it never had before. A big part of that was thanks to the leadership of people like Vanderbilt chancellors Gordon Gee and Nick Zeppos and athletic director David Williams. They understood that Perry had done more for the university than Vanderbilt ever did for Perry. So you saw things happen like Perry’s jersey retired, he was inducted into the inaugural class of the Vanderbilt Athletics Hall of Fame. Since the book came out in 2014, other things happened like various awards being named after Perry, scholarships established in his name, his induction into various other halls of fame and rings of honor. Vanderbilt freshmen all read STRONG INSIDE the last two years.

With the publication of the Young Adult version of the book, kids all over the country have learned his story and been inspired by it. It was gratifying that Perry got to experience this love and appreciation before he passed away. One thing that’s been interesting to observe is the way that Perry’s own family, especially his wife, Karen, has been able to witness the incredible affection that so many people had for Perry since his passing. He was such a humble and accomplished person he didn’t talk much about his “basketball pioneer days” to his family, friend and colleagues in D.C. There was a whole “public figure” aspect to his existence that was different from the Perry they knew every day: the professor, husband and father who was a regular guy and took out the trash every night.

Who are a half-dozen or so authors whose books are must-reads for you again and again?

Bill Bryson, John Feinstein, Bob Woodward, Eric Larson, James Swanson, Howard Bryant, Jeff Pearlman, Ruta Sepetys, Lou Moore and of course, David Maraniss!

In your opinion, who are some of the most important journalists whose articles and broadcasts are pertinent to understanding what’s happening in the world around us?

I will answer this question specifically as it relates to race and sports. First, I’d recommend anyone interested in the subject check out ESPN’s TheUndefeated.com site. It’s fantastic and right at the cutting edge of these issues. People like Lou Moore, Derrick White, Dave Zirin, Etan Thomas, Bijan Bayne, Anya Alvarez, Jemele Hill, Howard Bryant, Johnny Smith and Jesus Ortiz are must-follows on Twitter. We’ve also started a Twitter account at Vanderbilt called @raceandsportsVU that curates this kind of news.

What was the last great book you read?

For the book I’m writing on the first U.S. Olympic basketball team, I just read a German book on those Olympics that was recently released in an English translation. It’s called “Berlin 1936: Sixteen Days in August” by Oliver Hilmes, and it presents a really interesting look at some behind-the-scenes intrigue in Berlin at the time.

***

Follow Andrew Maraniss on Twitter: @trublu24

Visit his website: andrewmaraniss.com

Reblogged this on Ed Odeven Reporting.